Narrative - The Ned Kelly Story

Detailed below is the story of Ned Kelly. It has been well researched and reflects only factual information available from authentic sources.

Detailed below is the story of Ned Kelly. It has been well researched and reflects only factual information available from authentic sources.

DEDICATION

Dedicated to the memory of Sergeant Michael Kennedy, Constable Thomas Lonigan and Constable Michael Scanlan of Victoria Police who were brutally murdered by Edward (Ned) Kelly, Daniel (Dan) Kelly, Joseph Byrne and Stephen Hart, at Stringybark Creek, north of Mansfield, Victoria on the 26th October 1878.

They will not be forgotten.

INTRODUCTION:

The facts relating to Ned Kelly detailed in this narrative have been thoroughly and meticulously sourced from numerous historical writings and are based on fact. Although I have researched the Kelly era, I am indebted to others of like mind who sought the truth and found it and who have graciously permitted me to use their findings and references.

THE OUTLAW

Edward (Ned) Kelly was born in December 1854, at Beveridge, Victoria, to Ellen (nee Quinn) and John (Red) Kelly. He was born into a criminal family, with both sides of his parentage well acquainted with criminal activity. As he grew many of his near relatives were charged with various offences and terms of imprisonment were frequent. Ned learnt well from his relatives and soon became adept in the criminal activities of his clan. Among his achievements, he had become a skilled liar, a prerequisite for any criminal. One of his initial mentors was Harry Power, an escaped convict from Melbourne, who incidentally Ned gave up after doing a deal with the police, where charges against him were withdrawn.

The Kelly's had almost carte blanche to set up their criminal enterprise which they did with gusto, due to the lack of police in the area. A sophisticated chain existed up to the NSW border and beyond; involving several criminal entities that together had quite a profitable horse-stealing enterprise operating. During the Kelly, Quinn and Lloyd families' reign of criminal activity, members of the clans involved were very active in robbing almost anyone within their grasp. Stealing horses and cattle were among their favourite criminal pastimes. During that era, Ned Kelly was stealing a great number of horses and established a strong network of supporters to complete his criminal escapades and to report on police activity. Ned Kelly practised his criminal life for a decade before he was finally captured at Glenrowan. He was hanged on the 11th November 1880 for murdering Constable Lonigan at Stringybark Creek, north of Mansfield, Victoria.

THE ADULATION OF KELLY

The Greta Mob were running rampant in the 1870s and their criminal activities were well noted. Editorials in local papers were calling out this criminal activity and calling for police action to bring the criminals to heel. Due to the lack of police throughout Victoria, the criminal elements almost had a free hand and could pursue their criminal acts wherever and whenever they wished. After the siege at Glenrowan which brought the gang to an end, the population breathed a sigh of relief that the scourge had finally been removed. Papers across Victoria expressed their joy at the successful conclusion at the removal of the criminal elements.

The Melbourne Punch pulled no punches with what they said.

"The complete extermination of this band of cowardly murderers which was accomplished last Monday is a matter for sincere congratulation amongst all classes, and we hasten to offer our hearty thanks to those concerned in the annihilation of a national evil. To the prompt and decisive action of Mr. Ramsay, (Chief Secretary) and to the pluck and determination of Superintendent Hare and his brave associates, is due the fact that the country had been rid of the Kelly nightmare."

For more than fifty years Ned Kelly and his gang were reviled as they should have been, but there were always a few who lauded Ned Kelly and were prepared to promote him as a folk hero at any price.

The aura surrounding Ned Kelly began to expand around 1930 when there began to appear writings and books lauding this criminal, calling him a "Robin Hood" figure, who was robbing from the rich and giving to the poor. He was presented as standing up against police and government oppression, as his family was always being abused by police on false charges because they were Irish and Catholic. There was the bizarre suggestion that Ned was planning a rebellion to form an independent republic in North East Victoria. The suggestion was made that Constable Fitzpatrick who went to the Kelly home to execute a warrant on Dan Kelly for horse stealing had arrived there drunk and had tried to rape the fourteen-year-old Kate Kelly, Ned's sister. As you will see from the facts penned below that all of these scenarios are just made up fiction if not by the Kelly's themselves, by authors sympathetic to their cause, and designed to glorify one of this nations worst criminals and there is, in fact, no truth to any of them. Sadly, a large section of the population now believes this nonsense, and Kelly is considered a victim rather than an aggressor and he is considered by many to have been oppressed and forced into being a criminal. One only has to view government websites relating to Kelly to see the adulation and falsehoods that are promoted that present the police as the aggressors, rather than the real aggressor, that being Ned Kelly himself. This adulation is misplaced and needs to be corrected.

For more detailed information on the mythical North East Republic. CLICK HERE

A LAWLESS BUNCH

The Greta Mob generally came from three family groups, the Kelly's, the Lloyd's and the Quinn's, along with a few others of similar ilk who were mostly domiciled in the Greta region and wider, north of Mansfield, Victoria. They could all properly be described as criminal families and had intermarried extensively. To show they belonged to the Greta Mob chin straps were worn under the nose rather than under the chin by the young louts. This was done to intimidate decent law-abiding members of the community, similar to bikies of today wearing their colours.

The three families were lawless and at times quite vicious when dealing with other members of the public, and ironically, also among themselves. There were many more court appearances than those listed below, but these represent some of the more serious offences committed by the three lawless families.

In January 1868, just over a year after Red's death, his brother James arrived at Ellen Kelly's shanty in a drunken state and demanded sex from Ellen Kelly. She refused his advances and a violent argument resulted and in a fit of rage he set fire to Kelly's dilapidated shanty which was also used as a sly grog shop. There were 13 children in that home on the night and many were lucky to escape from being incinerated. This left Ellen Kelly and two of her sisters destitute after losing her husband. Her sister's husbands were both in gaol at the time.

The police were called and James Kelly was charged with attempted murder at the Beechworth Circuit Court. Judge Redmond Barry sentenced him to death which was the only option available to him. It is of interest to note that Judge Barry wrote to the Government suggesting that the penalty of death was too harsh and recommended that the Act be altered to a maximum term of 10 years. The Act was amended but to a term of 15 years. James Kelly received the benefit of that change and his sentence was commuted to 15 years.

In June 1869, Ned joins Harry Power in highway robbery.

In October 1869 at the age of 14 Ned was charged with robbing a Chinese trader. He spent two weeks in custody on remand, but eventually, the matter was not proceeded with due to Kelly producing two witnesses prepared to perjure themselves claiming that in fact, the Chinese trader assaulted him.

In May 1870, Ellen Kelly is charged with sly grog selling.

May 1870 Ned is charged with two counts of Highway Robbery in company with Harry Power. He escapes conviction on the first count due to the informant not being able to identify him, and on the second count, the informant could not be found. Ned is further charged at Keyneton with a third count of Highway Robbery with Power, but the police withdraw the charge after doing a deal with Ned who gave information as to where Power hides out in the bush. Power is subsequently arrested and Ned becomes known as a "black snake" for giving him up.

August 1870 Ned's uncle, Pat Quinn and Jimmy Quinn are gaoled. Pat for four years after brutally assaulting a police officer with a stirrup iron and Jimmy Quinn for three months for threatening language and assault.

October 1870, Ned is convicted of indecent assault and indecent behaviour after sending a childless woman a parcel containing a calf's testicles. He is gaoled for six months in Beechworth gaol and given a twelve-month good behaviour bond.

April 1871, Ned is charged with involvement in the theft of the Mansfield Post Master's horse. Later the same year he is charged with feloniously receiving the stolen horse and is sentenced to three years in gaol. Ned's brother in law, Alex Gunn, is also sentenced to three years for horse stealing.

In October 1871, Ellen Kelly wins a maintenance case against William Frost, the father of her illegitimate child, Ellen. The celebrations that followed included wild revelry and drunkenness in Beechworth streets for three days, riding horses at full gallop by Ellen Kelly and others through the town. The Kelly clan appears in court as a result.

February 1872 brought Jimmy Quinn junior before the court on a charge of grievous bodily harm. He is gaoled for three years. In November he returned to court charged with assaulting his sister, Margaret, who he bashed in a drunken state smashing her face and disfiguring her for life when she objected to his sexual advances towards Jane Graham who was staying with Margaret at the time. A further eighteen months is added to his previous three-year sentence. One week later Ellen Kelly and Jane Graham appear in court charged with receiving a stolen saddle. Both are acquitted.

In February 1873 John Lloyd is gaoled for four years over an impounding dispute, where he stole his neighbour's horse and brutally hacked the animal to death with a tomahawk.

In April 1873 Jim Kelly, Ned's younger brother aged 14 is convicted of cattle stealing and sentenced to five years in prison.

As can be seen, the Greta Mob were not pillars of their community.

A short time after the Stringybark Creek murders, the Benalla Ensign editorial stated:

"The Kelly family are notorious in this district and their names are as familiar as household words. The home of the family has been the rendezvous of thieves and criminals for years and indeed has been the centre of crime that almost surpasses belief. They lived on the Eleven Mile Creek between Winton and Greta and made a living by horse stealing and theft. They were surrounded by neighbours of the same bad reputation and it was notorious that to obtain evidence or arrest the accused owing to the network of confederates for miles around was almost impossible."

THE AUTHORITIES

Ned Kelly often complained bitterly of the way the family was treated by government authorities and of course the police because of their Catholic Irish heritage.

The facts, however, show a very different story. The independent colony of Victoria was proclaimed in 1851. English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh came to this new colony, mostly leaving old animosities behind. There was, of course, a sprinkling of released criminals who made their way to Victoria from Van Diemen's Land. (Tasmania) There was significant co-operation between ethnic groups, and in fact, there was very little of the old countries problems that surfaced. The second Premier of Victoria was John O'Shanassey, an Irishman who served two terms, and Charles Gavan Duffy, also an Irishman served as Premier in 1871. Only 14% of the population was ethnically Irish, so there was clearly no animus evident. Most citizens considered themselves Victorian first and most were cooperative in helping communities build a new life for themselves regardless of ethnic origin.

Church groups, including the Irish Catholics, English Protestants and Scottish Presbyterians all helped each other to build churches and schools that rural areas needed. Fundraising by Catholics was well attended by other religious groups and money was given. When other religious groups held fundraisers the Catholics attended and donated. The cooperation to help build the colony was most evident.

In the early years of the colony, wealthy squatters took up large sections of rural land, effectively denying many settlers of obtaining any land on which they could make a living. The government recognised this quite quickly and the Lands Act was proclaimed in 1860, and that was supposed to address the issue. It failed and it took more than a decade to get it right and settled in favour of the settlers. Ellen Kelly herself applied for land at Eleven Mile Creek at Greta and was granted an 88-acre selection.

The Victoria police were not a well organised or effective force. It was undermanned, undertrained, and underpaid. Once a member had been accepted for employment he learnt his trade mostly from other police while on duty. There was little or no official training. He was issued with a sidearm but not instructed in its use. Many police could not use a firearm and if ammunition was expended the member was required to pay for it. Police generally went about in plain clothes as they had to buy their one and only uniform and they were expensive.

The Chief Commissioner, Captain Standish had a reputation for nepotism and there were serious problems with the upper echelons that created a toxic environment among senior ranks as the Royal Commission into the Victoria Police would later show. Victoria Police was mostly of Irish ethnicity with 82% of the officers having an Irish background. In the North East region of Victoria, there were only 50 mounted constables to service 11,000 square miles (28,000 sq. km). This gave criminal elements almost a free hand to carry out their trade unimpeded and they relished the opportunity to build criminal empires mainly from stock theft. The Kelly clan took full advantage of the circumstances that were presented.

The Kelly's consistently complained about police persecution during their many dealings with the police. The Royal Commission into the Victoria Police held in 1881 after the Kelly menace had been removed from society put that allegation to sleep very effectively with this comment.

"It may also be mentioned that the charge of persecution of the family by the members of the police force has been frequently urged in extenuation of the crimes of the outlaws; but, after careful examination, your Commissioners have arrived at the conclusion that the police, in their dealings with the Kelly's and their relations, were simply desirous of discharging their duty conscientiously; and that no evidence has been adduced to support the allegation that either the outlaws or their friends were subjected to persecution or unnecessary annoyance at the hands of the police."

CONSTABLE FITZPATRICK ARRIVES

Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick has been vilified over the years as being a drunken playboy, who, among other things went to the Kelly homestead drunk, and attempted to rape 14-year-old Kate Kelly. The Kelly clan claimed that this event started the events that led to the murder of the three police officers at Stringybark Creek. Fitzpatrick was eventually unceremoniously dismissed from the Victoria Police without a reason being given. When the facts are examined a very different picture emerges.

Constable Fitzpatrick was stationed at Benalla and had been assigned to relieve the permanent officer at Greta for a few days. He was aware that he would go directly past Kelly's place and he knew that a warrant had been issued for Dan Kelly on a charge of horse stealing. He considered it would be prudent for him to visit and perhaps arrest Dan on the warrant. He discussed the matter with his sergeant at Benalla who agreed with what Fitzpatrick planned, advising him to be careful. It should be noted that no instruction had been issued from senior officers regarding police not to attend Kelly's alone.

Fitzpatrick had previous dealing with some of the Kelly's, including Ned, and was on reasonable terms with them. He did not consider himself to be in any real danger attending there. The officer stopped at the hotel in Winton en route and had a drink of brandy and lemonade. One drink only then continued his journey. When he arrived at the Kelly's he spoke with Ellen Kelly, the matriarch of the clan for about an hour. He advised her he was looking for Dan as a warrant had been issued for his arrest. As he was riding away from the homestead he noticed two horsemen moving towards the home. He caught up with them at the horse paddocks but only one man was there at that time. It was William Skillion an associate of the Kelly's. Fitzpatrick asked who the other man was but Skillion refused to name the other rider. He rode back to the homestead and as he arrived called out for Dan. Dan Kelly came from the front door with a knife and fork in his hands. The officer advised him of the warrant and that he would have to go with him, under arrest. Dan was relaxed and asked if he could have some food first as he had been in the saddle all day. Fitzpatrick agreed to this and went inside with Dan. Kelly knew that he was not involved in this incident and would eventually be cleared as his alleged co-offender Jack Lloyd was.

Ellen Kelly, Kate Kelly and two other younger girls were present. Ellen Kelly whispered to the two smaller girls and they quickly ran out the back. Ellen Kelly then began to abuse the officer who was standing alongside Dan as he was eating. In a moment Ned Kelly entered by the front door and immediately fired a shot towards Fitzpatrick. The first shot missed. Kelly fired a second shot that hit the officer just above his left wrist. At the same time, Ellen Kelly took a fire shovel and smashed it over the officer's head. Fortunately, he was still wearing his helmet, which took the brunt of the blow, but it was still enough to knock the officer senseless. Fitzpatrick being very close to Ned Kelly, grabbed at Ned's pistol trying to disarm him. A third shot was fired that also missed, and it was at this time that Fitzpatrick reached for his weapon, only to find that Dan had removed it from its holster and was holding it pointing at him. Ned, now realizing who the officer was stopped his attack and called on others to do the same. Both Skillion and Williamson were armed with pistols in their hands when they entered.

Fitzpatrick, who was both dazed and losing blood from his wound fainted and fell to the floor. As he regained his senses he heard those who had assailed him talking about what to do. Eventually, the officer himself removed the projectile from his wrist, and it was bound by Ellen Kelly. Ned Kelly initially refused to let the officer go but allowed him to leave sometime later near 11 pm. Fitzpatrick had enough strength to leave and mounted his horse. He had recovered his pistol but Ned had kept the ammunition. He had ridden about two miles when he thought he saw Skillion and Williamson about 100 yards behind him, having caught up to him. He spurred onto the hotel at Winton where he was assisted inside by the owner and his brother as he could no longer stand on his own. David Winton, the hotel owner attested that Fitzpatrick was sober when he arrived at the hotel. Assisting the officer to recover and re-bandaging the wound, Winton offered Fitzpatrick brandy which he at first refused but later took the brandy. Winton rode with the officer back to Benalla. They arrived at about 2 am. The next evening police attended the Kelly's and arrested Ellen Kelly, William Skillion and William Williamson for aiding and abetting the attempted murder of Constable Fitzpatrick.

Warrants were issued for Ned Kelly for attempted murder and for Dan Kelly for aiding and abetting. Ellen had an infant in her arms at the time. They were all found guilty and Ellen was sentenced to three years gaol, with both Skillion and Williamson received six-year terms. They were sentenced by Judge Redmond Barry, who was intending to send a strong message to the criminals of the region. The sentences were indeed severe, as senior police at the time commented. It should be noted that Ellen Kelly at her trial would have had an excellent excuse for her behaviour if Fitzpatrick had tried to take liberties with Kate Kelly. Nothing was mentioned at her trial of this nature. It was almost a year after the event that the first record of Kate Kelly suggesting that Fitzpatrick had acted improperly towards her surfaces. It was, of course, made up to discredit Fitzpatrick, and that has led to numerous authors accepting the allegation as truth when in fact it was a fabrication and easily dismissed as such.

Ned Kelly denied on numerous occasions that he was even there, claiming to be 20 miles, 200 miles and finally 400 miles from Greta (The Gerilderie letter) when this incident occurred. The Kelly clan made up stories to discredit Fitzpatrick and some of those lies were taken up by authors sympathetic to Kelly, who ignored Kelly’s reputation as a compulsive liar and were widely promulgated. They ignored the fact that the Kelly clan was skilled at lying, and they were skilled at making up stories to suit their circumstances demonizing the police. So much fiction now appears in written material the lies have, to some extent, become 'facts.' Ultimately Ned admitted both to police and journalists after his capture that he was there and that it was he who shot Fitzpatrick. William Williamson, who was present in the room at the time corroborated Fitzpatrick's affidavit and agreed that it was accurate when interviewed by the Chief Commissioner of Police Standish while he was in gaol.

Also under oath, during Ned Kelly's trial in Melbourne, Senior Constable Kelly described a conversation he had with Ned Kelly immediately after he had been captured at Glenrowan:

"Between 3 and 6 the same morning had another conversation with prisoner in the presence of Constable Ryan. Gave him some milk-and-water. Asked him if Fitzpatrick's statement was correct." Prisoner said, "Yes, I shot him."

After Kelly was captured he was interviewed by a journalist from the Age.

"Reporter: Now Kelly, what is the real history of Fitzpatrick's business? Did he ever try to take liberties with your sister Kate?" "Kelly: No that is a foolish story. If he or any other policeman tried to take liberties with my sister, Victoria would not hold him" (The Age, August 9th 1880)

Ellen Kelly decades later also confirmed that Fitzpatrick's version was essentially correct and there was no improper approach to Kate Kelly Constable Fitzpatrick was performing his duty correctly and his depositions were truthful.

He has been vilified for far too long for simply doing his duty responsibly.

The Ned Kelly tourist route guide that is widely distributed throughout Kelly country today states the following.

"Fitzpatrick, newly arrived, rode out to the Kelly house with a belly full of booze and glory on his mind - either from making a conquest of Kate or bringing in Dan."

It is false comments like these that are promoted in government documents that need to be corrected and replaced with facts.

For further more detailed information re the Fitzpatrick matter. CLICK HERE

THE MURDERS AT STRINGYBARK CREEK

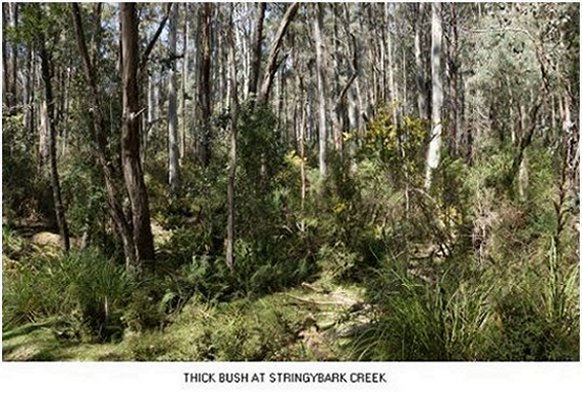

Following the incident with Fitzpatrick at the Kelly home police stepped up their efforts to capture the two Kelly brothers. It was well known that they would hide in the Wombat Ranges east of Greta, and many hiding places in the ranges were very heavily timbered with extensive ground cover. Visibility in the dense bushland was extremely difficult and it was almost impossible in most places to see more than a few metres ahead. It was a perfect natural hideout for the gang, and they took full advantage.

Senior police arranged for two mounted parties to head into the Wombat Ranges in an attempt to capture both Ned and Dan Kelly. One group would start from Mansfield and head north while the other would start from Benalla and head south. The Mansfield group would be headed by Sgt. Michael Kennedy, an officer with some fourteen years' experience. He would be joined by Const. Lonigan, who could recognise the Kelly's, Constable Scanlan, who was familiar with the bush, and Const. McIntyre.

The mission was to be kept secret and early on the morning of Friday 25th October 1878, they left Mansfield and headed north. Before leaving Sgt. Kennedy spent some time with his 5 children and his pregnant wife Bridget. Constable Lonigan, who had four children and his wife Charlotte was pregnant with their fifth had ridden from Violet Town to join the group at Mansfield. As he left Violet Town he turned and rode back twice to say goodbye to his children and his wife. Lonigan reputedly returned, perhaps three times in total to hug his children and wife. All the officers knew they were on a dangerous mission. They were armed with their service pistols and had borrowed a doubled barrel shotgun (fowling piece) from a local minister, and also a Spencer rifle loaned from a gold escort. They carried two sets of handcuffs to use on the two brothers if caught. They had two packhorses that carried a borrowed tent and provisions. Kelly enthusiasts claim that they carried body bags and other equipment to carry dead bodies and that the police had claimed they were going to shoot and kill the Kelly's on site. This scenario is fiction and made up to denigrate the police who were acting with proper intent to arrest the Kelly brothers and bring them to justice.

The officers reached Stringybark Creek late in the afternoon and decided to camp the night there. They did not post a guard, as they should have, as clearly they did not know that they had camped within perhaps two kilometres from the Kelly hut where the brothers and Joe Byrne and Steve Hart were hiding. The next morning Sgt Kennedy and Constable Scanlan rode out to search the area leaving McIntyre and Lonigan in the camp. Around noon McIntyre took the shotgun and headed towards the creek and fired at some parrots hoping to snare some food. He returned to the camp and placed the shotgun in the tent. His pistol was also in the tent. Lonigan was somewhat uneasy and kept his weapon on his hip.

At the murder trial of Ned Kelly Constable McIntyre gave the following evidence.

"We were standing at the fire with one of the logs between us. Lonigan alone was armed and he only had a revolver in his belt. My revolver and fowling-piece were in the tent. There was a quantity of spear grass 5ft. high about 35 yards from the fire, and on the south side of the clearing. I was standing with my face to the fire and my back to the spear grass when suddenly several voices from the spear grass sang out, "Bail up, hold up your hands." Turning quickly round, I saw four men, each armed with a gun, and pointing these weapons at Lonigan and me. The prisoner, who was one of the men, had the right-hand position, and he had his gun pointed at my chest. I, being unarmed, at once threw my arms out horizontally. Lonigan was in my rear and to my left. Saw the prisoner move his rifle, bringing it in a line with Lonigan and fire. By glancing round I saw that the shot had taken effect on Lonigan, for he fell. A few seconds afterwards he exclaimed, "Oh, Christ, I'm shot."

(There were no official depositions taken at the trial of Ned Kelly and this report comes from journalists taking notes in the court at the time.)

The round hit Lonigan in his right eye and it entered his brain resulting in almost instant death. The post mortem revealed that Lonigan had four bullet wounds. One went through his right eye, the fatal shot, another to his right temple, with further wounds to his right arm and left thigh. Clearly, Lonigan was standing up either facing Kelly or trying to run to cover. Kelly's version was that Lonigan ran and hid behind a fallen log and he rose to fire at Kelly when Kelly fired his rifle hitting Lonigan in the head. McIntyre stated that Lonigan had not drawn his sidearm when Kelly murdered him while he was still standing up behind him. Kelly spoke at length with McIntyre and learnt that there was, in fact, four police in the party.

McIntyre continued his evidence at the trial relating to the murder of Constable Scanlan by Kelly.

"Kennedy and Scanlan came up on horseback. They were 130 yards from us. The prisoner was still kneeling behind the log. He stooped to pick up a gun. Kennedy was on horseback. Prisoner said, "You go and sit down on that log" (pointing to one), and added "Mind you don't give any alarm, or I'll put a hole through you." The log was about 10 yards distant from the prisoner, in the direction of Kennedy. When they were 40 yards from the camp I went to them and said, "Sergeant, we are surrounded; I think you had better surrender." Prisoner at the same time rose and said "bail up." Kennedy smiled, and thought it was a joke. He put his hand on his revolver. As he did so prisoner fired at him. The shot did not take effect. The three others came from their hiding place with their guns, and cried out, "Bail up." Prisoner picked up the other gun. Scanlan when Kennedy was fired at, was in the act of dismounting. He became somewhat flurried and fell on his knees. The whole party fired at him. Scanlan received a shot under the right arm. He fell on his side. Kennedy threw himself on the horse's neck, and rolled off on the offside, putting the horse between him and the prisoner."

Kelly claimed that Scanlan had fired twice at him with the rifle from behind cover before he returned fire. Constable McIntyre had a clear view of this and refuted Kelly's version. The post mortem of Scanlan revealed wounds to the right shoulder, the top of the sternum, chest and right hip. Scanlan did not have a weapon in hand when he was murdered by Kelly. Kelly enthusiasts claim there was a gunfight at Stringybark Creek. Up to this time, there was no gunfight. It was just cold-blooded murder.

The Kelly gang now turned their attention towards Sgt. Kennedy has slipped off his horse on the opposite side in the direction of the attack. Kennedy's horse moved away and McIntyre was able to catch it and in a scramble mount and make an escape with the Kelly crew firing volleys after him. McIntyre thought that he saw Sgt. Kennedy drop his pistol after being wounded in the initial shots coming from the Kelly's after he dismounted but he was not sure and claimed he could not swear on oath that it had occurred. From this point, we only have Kelly's version of events. His version of Lonigan and Scanlan was disproved by McIntyre, so the version regarding Kennedy is almost certain to be fictitious. Kelly claimed that Kennedy was running and hiding behind trees and shooting at him and his gang. He did acknowledge that when he shot Kennedy in his right chest and he fell, he was not holding a weapon. We simply do not know if he dropped his weapon during the first contact or later as he was trying to escape the four gang members who were each armed with a pistol and a rifle or shotgun and pursuing him through the bush and firing at him. Ned Kelly approached the fallen officer and a conversation took place. Kennedy asked to be left alone as he had five children and his wife was pregnant and he wanted to see them before he died. Kelly raised the shotgun and at point-blank range blasted Sgt. Kennedy in the chest killing him instantly. Kelly would later boast to his hostages at Euroa that he killed Kennedy in a fair fight.

About two miles from the campsite the horse McIntyre was riding was spent. He abandoned the horse and was scared that the gang would come after him, which they did as he heard voices. Hiding in a wombat hole he waiting until it was very dark before he headed off towards civilisation. Walking back to Mansfield took him most of the night and day but eventually, he came to the outskirts of the town and received assistance. He went straight to the home of Sub Inspector Pewtress and reported the murders. It was late in the afternoon but a police and civilian volunteer party was put together and they headed for Stringybark Creek.

In the meantime the Kelly's had returned to the campsite and robbed the corpses, turning out the pockets of the deceased officers. Sgt Kennedy was robbed of money and a gold watch which was a family heirloom. They then burnt the tent, took the weapons, ammunition and stores along with the horses and disappeared.

The police party reached the site of the murders very late in the afternoon and camped there overnight. In the early morning light, they secured the bodies of Constables Lonigan and Scanlan onto horses and a small party began the journey back to Mansfield. Sgt Kennedy had not yet been found and it took a further five days of extensive searching to find his mutilated body which was almost 800 metres from the campsite.

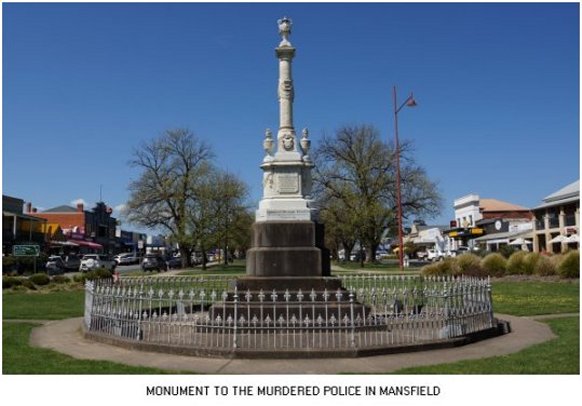

The colony of Victoria was horrified at the news of the murders at the hands of the Kelly's. The murders had left nine children without their fathers and left two pregnant widows in a destitute state. Fortunately, the government eventually agreed to pay a pension equivalent to the officers pay for life to the two widows. Funerals for the officers were held in Mansfield and attended by most residents of the town. They were buried in the Mansfield Cemetery relatively close to each other. All the slain officers were highly respected in their communities and the community quickly banded together to raise funds for a memorial to be erected in the officers. That memorial still stands in the centre of Mansfield today and is a centrepiece of the town. Ironically the Tourist Information site in Mansfield hands out a pamphlet denigrating police, while three of the most respected police officers to serve in northeast Victoria lie in the cemetery victims of Ned Kelly who is lauded in the same document.

THE EUROA BANK HOLD UP

Before the Stringybark murders police numbers had been reduced by government directives. It was a disaster as it allowed almost a free hand for the criminals to further expand their criminality. With limited resources police stepped up their efforts to capture the murderers but the gang had disappeared. For six weeks nothing was heard then on December 8th 1878 the Kelly gang held up the Bank in Euroa stealing a great deal of money. They had taken hostages, some 24 in total at the Faithfull Creek sheep station just outside Euroa which they used as a base to launch this audacious attack. The amount they stole is in question. It was somewhere between £ 1500 and £ 5,000, in gold and money. The hostages later reported that Kelly had boasted to them that he had shot all the police at Stringybark Creek, and it was here that Kelly stated to the hostages that he had killed Sgt. Kennedy in a fair fight. The government lifted the reward to £ 1,000 for each of the gang members.

After the holdup, the gang disappeared again. The police reacted by sending an NCO and six men to towns in the region in an attempt to stop further hold-ups. It was a futile attempt but the effort was much appreciated by the people living in those towns, as they felt themselves vulnerable to attack by the Kelly menace.

THE GERILDERIE BANK HOLD UP

The rural town of Jerilderie is situated some 36 miles north of the Murray River in New South Wales. Kelly had often travelled there while involved with stolen horses so he was familiar with the town. On the evening of 8th February 1879, the gang arrived at Mrs Davidson's Woolshed Inn where they had drinks, and near midnight they rode into town and took the town's two police officers hostage locking them in their lock-up. The officer in charge was Sen. Constable George Devine and his pregnant wife and their three children were held in the family sitting room. The next morning near 11 am the Kelly brothers dressed in police uniforms and in company with the hostage Constable Henry Richards walked down the main street to the Royal Mail Hotel, which also contained the bank and took hostages in the hotel locking them in a secure room. Kelly then entered the bank via the backdoor holding pistols in each hand to begin the holdup. From the bank, they stole some £ 2,141, and from the sixty or so hostages they held, valuables were stolen.

Samuel Gill the town's newspaper editor sensed something was amiss and went to the police station where he saw Mary Devine huddled together with her three children. She warned him his life was in danger and he ran quickly to Monash's store. (The Monash store was owned by the father of General Sir Thomas Monash who figured so prominently in the First World War) Gill was not believed so he took a horse and rode out to a property six miles out of town and tried to get a message to Deniliquin police.

Kelly intended to demand of the Editor that he publish a letter he had dictated to Byrne who had written it for him. The letter, now known as the Jerilderie letter, was designed to detail his version of events including his side of the story and his assertion that he and his family had been driven to a life of crime by police and government harassment. The full letter would not be seen by the public for fifty years after Kelly delivered it to Edward Living the bank teller that he had robbed instructing him to ensure the letter was published. Living handed the letter to the police after the gang left. Senior police having read the letter properly considered it a plethora of lies, as it was. Sadly, many Kelly enthusiasts have taken the Kelly lies to be facts and have repeated much of the myths that Kelly wrote to justify his criminal behaviour in books that have dominated the public view for far too long.

The robbery completed, Kelly ordered the telegraph poles to be cut down and threatened his hostages that if they were repaired he would return and kill those who disobeyed him. The gang had previously collected horses from the town and driven them out of town to ensure they could not be pursued. As soon as the gang left the townsfolk moved to collect weapons, horses and to repair the telegraph line. The line being repaired, telegrams were immediately sent to surrounding towns warning them to be alert. The Kelly gang disappeared and was not heard from for just over sixteen months. After this robbery the NSW and the Victorian governments raised the reward to £ 4,000 each, making the reward a total of. It was an enormous sum.

THE SIEGE AT GLENROWAN

For several months settlers and squatters in North East Victoria were reporting plough shares had been taken from their properties. Ipoundt was somewhat baffling as to why someone would steal a ploughshare, but police reports were duly taken. No one suspected what they would be used for, but the police and the public were soon to learn why they were stolen as events unfolded at Glenrowan.

We can only presume where Kelly and his gang were for those sixteen months, but almost certainly he was being supplied with food and other needs by his family and close associates. It appears that he was by now running out of money and decided to bring matters to a head at Glenrowan.

The police in their efforts to capture Kelly and his gang had asked Queensland Police for black trackers to assist in the search. Kelly was warned that they were in the area and it was clear that he was extremely cautious as he knew how well aboriginals could track. The black trackers were not used to their fullest extent due to conflicts at senior levels within the police force.

Kelly and his gang had become sick of having to hide all the time from the police who were by now active in their quest to bring him to justice and who had been close to capturing them on several occasions. (Kelly confirmed this to journalists after his capture) A plan was developed to murder Aaron Sherritt who was once a close friend of Byrne as he was considered a police spy. Kelly knew that this would bring the police by train from Benalla and they had devised a plan to rip up the train tracks and let the train derail and kill all the police, men, women and children who were on the train. The gang would stand up on the high ground and be able to shoot down on their victims while wearing the armour that they had fashioned from the stolen ploughshares. From their position, their legs could not be seen and they would be protected from any fire the police could return. After they had massacred the police then intended to ride to Benalla, blow up the police station and rob the banks. To say the least the plan was somewhat ambitious and has been described as hair-brained. That was an apt description as subsequent events would reveal.

On the evening of 26th June 1880 Dan Kelly and Joe Byrne having taken a neighbour Anton Wicks hostage, went to Sherritt's home where Wicks was told to knock on the back door and identify himself. Sherritt opened the door and was met with a burst of fire from Joe Byrne killing him instantly. Sherritt had recently married and the murder was committed insight of his pregnant wife. There were four police in the house at the time there to protect Sherritt, but they failed to move and it was some hours before they cautiously came from the bedroom in which they were hiding. The subsequent Royal Commission recommended they all be dismissed from the force. One has already resigned and the other three were dismissed. In the meantime, Ned Kelly and Steve Hart had ridden into Glenrowan during the evening of Saturday 26th June 1880. Later that night Kelly and Hart had gone to a site north of the town and attempted to tear up the railway tracks. They failed in their efforts as they had no equipment to undertake the task properly. With the Station Master and workmen taken as hostages, two rails were finally removed by 3 am on Sunday.

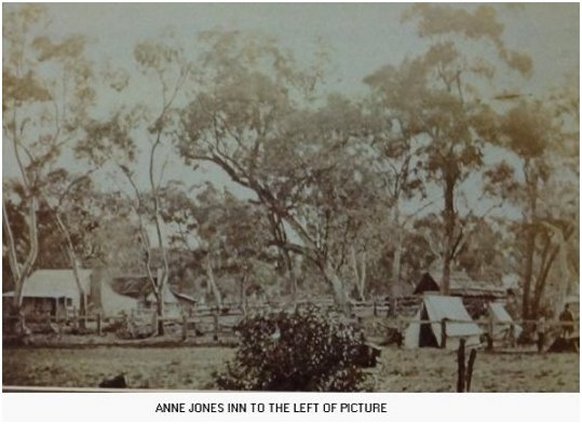

Kelly had expected a police train to come from Benalla with police, but again he miscalculated as the train was organised from Melbourne and it ultimately took some 31 hours to reach Glenrowan. Onboard from Benalla was Supt. Hare, seven police troopers, Inspector O'Connor (Qld. Police) with his five black trackers, one volunteer, two women, an engine driver, stoker and guard along with four members of the press. The delay caused great difficulty for Kelly. During the Sunday he had taken hostages and was keeping them in Anne Jones hotel, which was about 100 metres north of the railway station at Glenrowan. In total there were some 62 hostages including men women and children who Kelly kept while waiting for the police train to arrive. Dancing, card games, sporting events and singing were ordered while they waited for the police train to arrive. The gang had partaken of a fair amount of alcohol and as Anne Jones would later say, "They were all quite drunk." They were certainly sleep-deprived. During this time Ned Kelly was playing with a seized firearm and it accidentally discharged hitting the hostage George Metcalf in the eye. It was a serious wound but Kelly denied Metcalf any medical attention and he died from the wound some 2 months later.

For more detailed information on the George Metcalf incident CLICK HERE

At Benalla, the train stopped and the word was passed to Supt. Hare that the tracks may have been interfered with. Hare took the information seriously and arranged for an engine to precede the special police train. It should be noted that there were probably four Kelly sympathisers within the hotel to ensure the hostages were not planning a revolt. Thomas Curnow the local school teacher who had been taken hostage with his wife recognised the potential for the police and told Kelly that the station master had a pistol. The weapon being secured Kelly considered that Curnow was on side. Curnow asked to be let go as his wife was ill and Kelly gave his permission. As soon as his wife was secured in their home Curnow took a candle and a red handkerchief and walked back down the line in time to stop the first train and avoid what could have been a massacre of the police. The time was just after 3 am.

The second train carrying the police approached and stopped. Constable Bracken, the local police officer having escaped from the hotel ran towards the police group and told Supt. Hare that the gang was in the hotel. Hare with seven police, who were all in plain clothes, took off towards the hotel. In Supt. Hares report he would say that when 50-80 yards from the hotel a shot rang out hitting him in the left wrist. Further firing then came from the verandah of the hotel with all four gang members firing at the police, all clad in their armoured suits. The officers who were then present returned fire hitting Ned Kelly in his left wrist with the round exiting at the elbow and he was also hit in his right foot. His left arm being useless he with the other gang members retreated inside the hotel. Supt Hare instructed his men to surround the hotel, but this took time as initially some of the police were unloading horses from the train and it took some minutes before they could join the fray. Police numbers at the hotel were limited and it took some time to surround the hotel to prevent the outlaws from escaping. It was brought to Hares attention that there were hostages inside, so he instructed his men to shoot high to avoid the hostages. Hearing screams from women and children coming from the hotel, Hare ordered a ceasefire before he was forced to leave the scene. To some extent, his order was ignored or not received by some police. The firing from both sides continued unabated. Hare's wound was bleeding profusely and he was forced to withdraw to seek medical attention. He made his way to the railway station, leaving Queensland Inspector O’Connor in charge. Messages had been sent and extra police were on their way from Benalla, Wangaratta, Beechworth and Violet Town.

There is confusing information as to what Ned Kelly did after the initial clash, but he probably walked straight out the back of the hotel, as the Royal Commission commented, for some 150 metres, dropping a rifle covered with blood at 100 metres or so, and lay down behind a fallen log as he was quite seriously wounded. There are claims that he mounted his grey mare and rode to warn off his supporters, but with heavy armour and with one arm useless and his foot badly injured this is almost certainly impossible. With the circumstances presented he would not be capable of mounting a horse. Kelly said that he had returned to the hotel through police lines and saw Joe Byrne shot dead. A likely story and almost certainly another Kelly lie. Joe Byrne was hit by a police bullet near 5 am according to the prisoners in the shootout with Byrne receiving a wound to his groin as his armour did not cover this area adequately. He bled to death from the loss of blood.

Perhaps one of the best descriptions of what occurred at Glenrowan was written by one of the journalists who came from Melbourne on the police train. It is repeated verbatim as it appeared in the Melbourne Argus on Tuesday 29th June 1880.

"Benalla was reached at half-past 1 o'clock, and there Superintendent Hare with eight troopers and their horses were taken on board. We were now about to enter the Kelly country and caution was necessary. As the moon was shining brightly, a man was tied on upon the front of the engine to keep a look-out for any obstruction of the line. Just before starting, however, it occurred to the authorities that it would be advisable to send a pilot engine in advance, and the man on the front of our engine was relieved.

A start was made from Benalla at 2 o'clock, and at 23 minutes to 3 when we were travelling at a rapid pace, we were stopped by the pilot engine. This stoppage occurred at Playford and Desoyre's paddocks, about a mile and a quarter from Glenrowan. A man had met the pilot and informed the driver that the rails were torn up about a mile and a half beyond Glenrowan and that the Kelly's were waiting for us near at hand. Superintendent Hare at once ordered the carriage doors on each side to be unlocked and his men to be in readiness. His orders were punctually obeyed and the lights were extinguished. Mr Hare then mounted the pilot-engine, along with a constable, and advanced. After some time he returned, and directions were given for the train to push on. Accordingly we followed the pilot up to Glenrowan station, and disembarked.

THE FIRST ENCOUNTER.

No sooner were we out of the train, than Constable Bracken, the local policeman, rushed into our midst, and stated with an amount of excitement which was excusable under the circumstances, that he had just escaped from the Kelly's, and that they were at that moment in possession of Jones's public house, about a hundred yards from the station. He called upon the police to surround the house, and his advice was followed without delay. Superintendent Hare with his men and Sub-inspector Connor with his black trackers, at once, advanced on the building. They were accompanied by Mr Rawlins, a volunteer from Benalla, who did good service. Mr Hare took the lead and charged right up to the hotel. At the station were the reporters of the Melbourne press, Mr Carrington, of The Sketcher, and the two ladies who had accompanied us. The latter behaved with admirable courage, never betraying a symptom of fear, although bullets were whizzing about the station and striking the building and train. The first brush was exceedingly hot.

The police and the gang blazed away at each other in the darkness furiously. It lasted for about a quarter of an hour, and during that time there was nothing but a succession of flashes and reports, the pinging of bullets in the air, and the shrieks of women who had been made prisoners in the hotel. Then there was a lull, but nothing could be seen for a minute or two in consequence of the smoke. In a few minutes, Superintendent Hare returned to the railway station with a shattered wrist. The first shot fired by the gang had passed through his left wrist. He bled profusely from the wound, but Mr Carrington, an artist of The Sketcher, tied up the wound with his handkerchief and checked the haemorrhage. Mr Hare then set out again for the fray and cheered his men on as well as he could, but he gradually became so weak from loss of blood that he had reluctantly to retire and was soon afterwards conveyed to Benalla by a special engine. The bullet passed right through his wrist, and it is doubtful if he will ever recover the use of his left hand.

On his departure Sub-Inspector O'Connor and Senior-constable Kelly took charge and kept pelting away at the outlaws all the morning. Mr O'Connor took up a position in a small creek in front of the hotel, and disposed his black-fellows one on each side, and stuck to this post gallantly throughout the whole encounter. The trackers also stood the baptism of fire with fortitude, never flinching for one instant. At about 5 a.m. a heart-rending wail of grief ascended from the hotel. The voice was easily distinguished as that of Mrs Jones, the landlady. Mrs Jones was lamenting the fate of her son, who had been shot in the back, as she supposed, fatally. She came out from the hotel crying bitterly and wandered into the bush on several occasions, and nature seemed to echo her grief. She always returned, however, to the hotel, until she succeeded, with the assistance of one of the prisoners, in removing her wounded boy from the building, and in sending him on to Wangaratta for medical treatment.

The firing continued intermittently, as occasion served, and bullets were continually heard coursing through the air. Several lodged in the station buildings, and a few struck the train. By this time the hotel was surrounded by the police and the black trackers and a vigilant watch of the hotel was kept up during the dark hours. At daybreak, police reinforcements arrived from Benalla, Beechworth, and Wangaratta. Superintendent Sadlier came from Benalla with nine more men, and Sergeant Steele, of Wangaratta, with six, thus augmenting the besieging force to about 30 men. Before daylight, Senior-constable Kelly found a revolving rifle and a cap lying in the bush, about 100 yards from the hotel. The rifle was covered with blood and a pool of blood lay near it. This was the property of one of the bushrangers, and a suspicion there-fore arose that they had escaped. That these articles not only belonged to one of the outlaws but to Ned Kelly himself was soon proved. When the day was dawning the women and children who had been made prisoners in the hotel were allowed to depart. They were, however, challenged individually as they approached the police line, for it was thought that the outlaws might attempt to escape under some disguise.

CAPTURE OF NED KELLY.

At daylight the gang were expected to make a sally out, to escape, if possible, to their native ranges, and the police were consequently on the alert. Close attention was paid to the hotel, as it was taken for granted that the whole gang were there. To the surprise of the police, however, they soon found themselves attacked from the rear by a man dressed in a long grey overcoat and wearing an iron mask. The appearance of the man presented an anomaly, but a little scrutiny of his appearance and behaviour soon showed that it was the veritable leader of the gang, Ned Kelly himself. On further observation, it was seen that he was only armed with a revolver. He, however, walked coolly from tree to tree, and received the fire of the police with the utmost indifference, returning a shot from his revolver when a good opportunity presented itself. Three men went for him, viz., Sergeant Steele of Wangaratta, Senior-Constable Kelly, and a railway guard named Dowsett. The latter, however, was only armed with a revolver.

They fired at him persistently, but to their surprise with no effect. He seemed bullet-proof. It then occurred to Sergeant Steele that the fellow was encased in mail, and he then aimed at the outlaw's legs. His first shot of that kind made Ned stagger, and the second brought him to the ground with the cry, "I am done - I am done." Steele rushed up along with Senior-constable Kelly and others. The outlaw howled like a wild beast brought to bay and swore at the police. He was first seized by Steele, and as that officer grappled with him he fired off another charge from his revolver. This shot was intended for Steele, but from the smart way in which he secured the murderer, the sergeant escaped. Kelly became gradually quiet, and it was soon found that he had been utterly disabled. He had been shot in the left foot, left leg, right hand, left arm, and twice in the region of the groin. But no bullet had penetrated his armour. Having been divested of his armour he was carried down to the railway station and placed in a guard's van. Subsequently, he was removed to the stationmaster's office, and his wounds were dressed there by Dr Nicholson, of Benalla. What statements he made are given below.

THE SIEGE CONTINUED.

In the meantime the siege was continued without intermission. That the three other outlaws were still in the house was

confirmed by remarks made by Ned, who said they would fight to the last, and would never give in. The interest and excitement were consequently heightened. The Kelly gang were at last in the grasp of the police and their leader was captured. The female prisoners who escaped during the morning gave corroboration of the fact that Dan Kelly, Byrne, and Hart were still in the house. A rumour got abroad that Byrne was shot when drinking a glass of whisky at the bar of the hotel about half-past 5 a.m., and the report afterwards turned out to be true. The remaining two kept up a steady defence from the rear of the building during the forenoon and exposed themselves recklessly to the bullets of the police. They, however, were also clad in mail, and the shot took no effect. At 10 o'clock a white flag or handkerchief was held out at the front door, and immediately afterwards about 30 men, all prisoners, sallied forth holding up their hands. They escaped whilst Dan Kelly and Hart were defending the back door.

The police rallied up towards them with their arms ready and called upon them to stand. The crowd did so, and in obedience to a subsequent order fell prone on the ground. They were passed, one by one, and two of them - brothers named M'Auliffe - were arrested as Kelly sympathisers. The precaution thus taken was highly necessary, as the remaining outlaws might have been amongst them.

The scene presented when they were all lying on the ground, and demonstrating the respectability of their characters, was unique and, to some degree, amusing.

THE END - THE HOTEL BURNT.

The siege was kept up all the forenoon and till nearly 3 p.m. Sometime before this the shooting from the hotel had ceased and opinions were divided as to whether Dan Kelly and Hart were reserving their ammunition or were dead. The best part of the day had elapsed, the police, who were now acting under the direction of Superintendent Sadlier, determined that a decisive step should be taken. At 10 minutes to 3 o'clock another and the last volley was fired into the hotel, and under cover of the fire Senior-constable Charles Johnson, of Violet Town, ran up to the house with a bundle of straw which (having set fire to) he placed on the ground at the west side of the building. This was a moment of intense excitement, and all hearts were relieved when Johnson was seen to regain uninjured the shelter he had left.

All eyes were now fixed on the silent building, and the circle of besiegers began to close in rapidly on it, some dodging from tree to tree, and many, fully persuaded that everyone in the hotel must be ready for combat, coming out boldly into the open. Just at this juncture Mrs Skilling, sister of the Kellys, attempted to approach the house from the front. She had on a black riding habit, with a red underskirt, and white Gainsborough hat, and was a prominent object in the scene. Her arrival on the ground was almost simultaneous with the attempt to fire the building. Her object in trying to reach the house was apparently to induce the survivors, if any, to come out and surrender. The police, however, ordered her to stop. She obeyed the order, but very reluctantly, and, standing still, called out that some of the police were ordering her to go on and others to stop. She, however, went to where a knot of the besiegers was standing on the west side of the house. In the meantime, the straw, which burned fiercely, had all been consumed, and at first, doubts were entertained as to whether Senior-constable Johnson's exploit had been successful. Not very many minutes elapsed, however, before smoke was seen coming out of the roof, and flames were discerned through the front window on the western side. A light westerly wind was blowing at the time, and this carried the flames from the straw underneath the wall and into the house, and as the building was lined with calico, the fire spread rapidly. Still, no sign of life appeared in the building.

When the house was seen to be fairly on fire, Father Gibney, who had previously started for it but had been stopped by the police, walked up to the front door and entered it. By this time the patience of the besiegers was exhausted, and they all, regardless of shelter, rushed to the building. Father Gibney, at much personal risk from the flames, hurried into a room to the left and there saw two bodies lying side by side on their backs. He touched them and found life was extinct in each. These were the bodies of Dan Kelly and Hart and the rev. gentleman expressed the opinion, based on their position, that they must have killed one another. Whether they killed one another or whether both or one committed suicide, or whether both being mortally wounded by the besiegers they determined to die side by side, will never be known. The priest had barely time to feel their bodies before the fire forced him to make a speedy exit from the room, and the flames had then made such rapid progress on the western side of the house that the few people who followed close on the rev. gentleman's heels dared not attempt to rescue the two bodies. It may be here stated that, after the house had been burned down, the two bodies were removed from the embers. They presented a horrible spectacle, nothing but the trunk and skull being left, and these almost burnt to a cinder. Their armour was found near them. About the remains, there was nothing to lead to identification, but the discovery of the armour near them and other circumstances render it impossible to be doubted that they were those of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart. The latter was a much smaller man than the younger Kelly, and this difference in size was noticeable in their remains. Constable Dwyer, by-the-bye, who followed Father Gibney into the hotel, states that he was near enough to the bodies to recognise Dan Kelly.

As to Byrne's body it was found in the entrance to the bar-room, which was on the east side of the house, and there was time to remove it from the building, but not before the right side was slightly scorched. This body likewise presented a dreadful appearance. It looked as if it had been ill-nourished. The face was black with smoke, and the arms were bent at right angles at the elbows, the stiffened joints below the elbows standing erect. The body was quite stiff, and its appearance and the position in which it was found corroborated the statement that Byrne died early yesterday morning. He is said to have received the fatal wound, which was in the groin while drinking a glass of whisky at the bar. He had a ring on his right hand which had belonged to Constable Scanlan, who was murdered by the gang on the Wombat Ranges. The body was dressed in a blue sack coat, tweed striped trousers, Crimean shirt, and very ill-fitting boots. Like Ned Kelly, Byrne wore a bushy beard.

In the outhouse or kitchen immediately behind the main building the old man Martin Cherry, who was one of the prisoners of the gang, and who was so severely wounded that he could not leave the house when the other prisoners left, was found still living, but in articulo mortis from a wound in the groin. He was promptly removed to a short distance from the burning hotel and laid on the ground when Father Gibney administered to him the last sacrament. Cherry was insensible and barely alive. He had suffered much during the day, and death released him from his sufferings within half an hour from the time when he was removed from the hotel. It was fortunate that he was not burned alive. Cherry, who was unmarried, was an old resident of the district and was employed as a platelayer, and resided about a mile from Glenrowan. He was born in Limerick, Ireland and was 60 years old. He is said by all who knew him to have been a quiet, harmless old man, and much regret was expressed at his death. He seems to have been shot by the attacking force, of course unintentionally."

Finally the Kelly Outbreak had come to a bloody conclusion.

There was much rejoicing across Victoria that the menace had finally been so comprehensively destroyed. Editorials were in praise of the final result. The Singleton Argus and Upper Hunter General Advocate wrote:

"Had society been ridded of a horde of hyenas, wolves and tigers, thirsting for human blood, the joy would scarcely have been greater than that felt at the hunting down of this band of unmitigated ruffians and murderers."

Ned Kelly was treated for his wounds and there was some recovery. He appeared in the Central Criminal Court on the 28th October 1880 before Justice Redmond Barry and was charged with the murder of Constable Thomas Lonigan at Stringybark Creek on 28th October 1878. Kelly pleaded "Not guilty." The evidence given by Constable McIntyre was devastating to Kelly and his testimony was strongly supported by Dr Reynolds who carried out the post mortem on Lonigan. The jury took less than thirty minutes to bring in a guilty verdict. Judge Barry sentenced Kelly to death.

Kelly was also charged with the murder of Constable Scanlan but that was not proceeded with. He was never charged with the murder of Sgt. Kennedy and no record exists as to why he was not charged. After he was found guilty and sentenced to death his overnight guard Senior Constable Johnston had a conversation with Kelly and he was asked if the evidence given by Const. McIntyre was correct. Kelly confirmed that it was correct, except he said that Scanlan was not on his knees when he was shot.

Ned Kelly never uttered one word of remorse for his actions after his capture. At 10 am on the morning of 11th November 1880 he was hanged at the Melbourne Gaol. If ever a criminal deserved his fate it was Ned Kelly.